Last summer while hunting for Asher's Blues (Celastrina asheri) in eastern Oregon, I collected six larvae from red osier dogwood (Cornus sericea) flowers at Bear Hollow Campground southeast of Fossil in Wheeler County, Oregon. I was hopeful that they might be asheri: the larvae were mostly green compared to the (usually) heavier-marked Celastrina echo (see my article for more examples). Shortly after bringing them home, one of the larvae started to stand out to me as "odd", it had two pink-brown spots in an odd location and was noticeably shiny compared to the velvety-matte appearance of the others. Searching through James & Nunnallee's Life Histories of Cascadia Butterflies, I found a similar-looking larva: Callophrys augustinus, the Brown Elfin! However, osier dogwood was not listed as a known larval food plant, which I soon verified from Dave Nunnallee and Jonathan Pelham that it had never been recorded for augustinus. As the larva grew, it developed an even more striking pattern, had large, raised bumps on each segment, and maintained a very shiny appearance. The pupa was also different: a wider abdomen, solid dark brown color, and not shiny, compared to the "skinny" and shiny, honey-brown colored pupae of Celastrina. The puzzling bit was that one other larva produced an identical pupa, yet that larva had been one of the least-marked larvae of the six. This led me to second-guess myself and wonder if perhaps these two were just a variation of echo or asheri, or if in fact both were augustinus exhibiting a different larval morph, possibly due it using osier dogwood.

All larvae were found on osier dogwood flowers, which were at a stage where they were just beginning to lose petals on some flower heads. I continued to feed the larvae on osier dogwood flowers and young seed pods until they pupated. Because there were only six larvae, I kept track of them all the way through by numbering 1 through 6.

|

| Celastrina echo (1, 3, 5, 6) and Callophrys augustinus (2, 4) pupae in October 2022. |

Most of my rearing experience is with Saturniidae, cocoons and pupae of which usually do well with only occasional misting through the winter. However, my experience rearing Celastrina asheri last year resulted in only about 50% adult emergence and almost half of those never fully expanding their wings. I had overwinter those between paper towels which I misted with water a few times through the winter. The temperature and humidity sensor I keep with all my overwintering pupae was usually between 30-50% humidity, only rising to around 60% for a couple days when they were misted. I started thinking about what happens in the wild, that Celastrina pupae overwinter in the leaf litter, usually buried under snow, and must become completely drenched during the spring snowmelt. In comparison, cocoons and some butterfly pupae (like swallowtails) tend to be attached to twigs or in cracks of bark and are more exposed to the elements but are never completely submerged. So for this round of overwintering, I wanted to construct something that would more closely mimic consistently damp leaf litter while also being free of parasites (i.e. not using regular potting soil or wild leaf litter). Remembering that some lepidopterists have used bricks or clay pots for overwintering, which help regulate temperature and humidity, I came up with a plan. I used a clean clay pot tray, filled it half way with orchid mix (small bark chips and perlite used for potting orchids), then fashioned a cardboard separator which I taped to the edge of the clay pot using gorilla tape. I then covered the bark with wet sphagnum moss which I had previously soaked in another container (it comes in dry, sterile packages for gardening and craft use). I placed the tray into a slightly bigger plastic plant tray and packed more wet sphagnum moss into the space around the edge. This was to help the clay pot stay damp longer rather than evaporating out through the bottom. Initially I also placed part of a paper towel in each section so I wouldn't lose the pupae down into the sphagnum moss (see photo above), but within a month it started to mold so I removed it and just carefully placed each pupa in a spot where it wouldn't fall into a larger space. I loosely covered the tray with a folded hand towel to help with temperature and humidity regulation, then put everything into a small mesh bug cage on my north-facing balcony in late October.

|

| Overwintering tray during construction |

The temp/humidity sensor was kept next to the tray under the towel. The relative humidity fluctuated with the temperature but was fairly steady between 50-70% all winter. Whenever it started staying around 50% or less, I added 1/4 to 1/2 cup of water around the edge of the tray. This happened maybe 3-4 times through the winter. Once I accidentally spilled a bunch of water into the tray to the point where all the pupae were floating. I thought for sure this whole thing was a stupid idea and I had just drowned them and wouldn't get anything to emerge. I poured off a little of the excess water but left the rest to soak into the moss. Another time during the winter, the temperatures dipped down to 17F, which is very cold for my SW WA area. With difficulty I resisted bringing the cage inside overnight, all the while thinking that for sure they would freeze those two or three days, but reminding myself that they came from a very cold part of Oregon and had to be able to survive temperatures even lower, even if they were insulated under several feet of snow all winter.

In early March I rolled the towel over to the side just in case anything decided to pop out on a warm day. With the spring flowers finally blooming and a couple days of 60F weather (and reports of a wild Celastrina echo being spotted in NW Washington), I got impatient and brought the cage inside ahead of the next several days of cool and rainy weather. Three days later three of the six emerged, quickly followed by the rest over this past week. All my fears were relieved and the identity of species revealed! Four Celastrina echo and two Callophrys augustinus, confirming a new larval food plant record for augustinus! Click on the images to view at full screen.

|

| Larva 1: Celastrina echo, female |

|

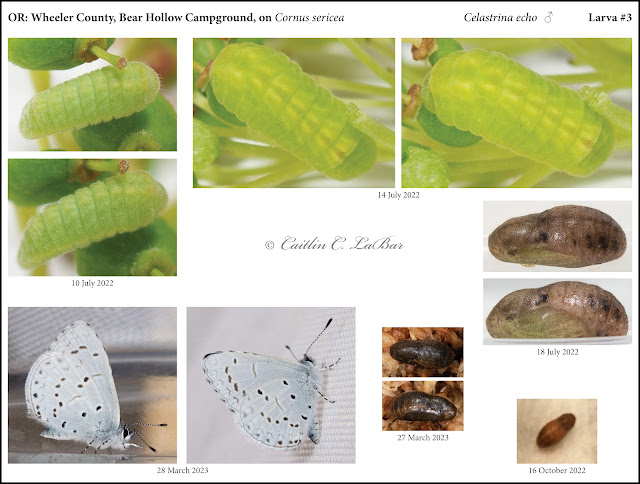

| Larva 3: Celastrina echo, male |

|

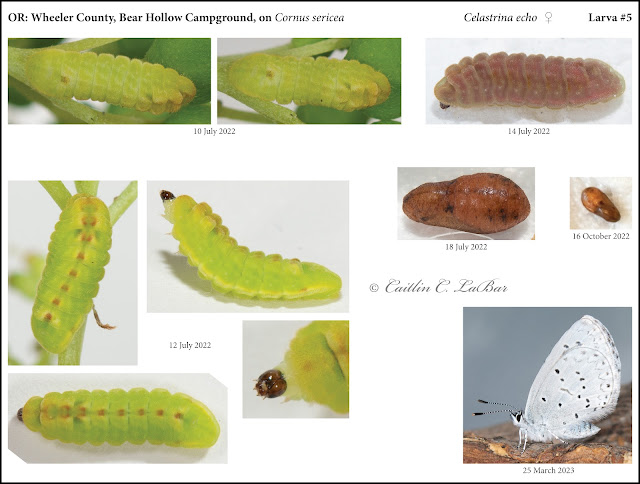

| Larva 5: Celastrina echo, female |

|

| Larva 6: Celastrina echo, female |

|

| Larva 2: Callophrys augustinus, male |

|

| Larva 4: Callophrys augustinus, female |

Reviewing the limited images of augustinus larvae, there are a few examples of solid green larvae, all from California and Arizona:

https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/2723370

https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/89286157

https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/2717237

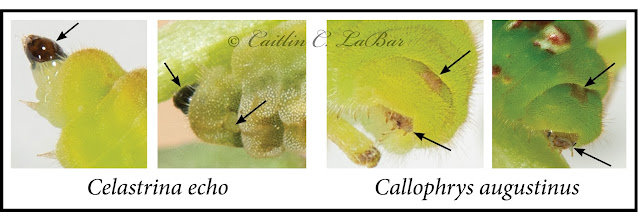

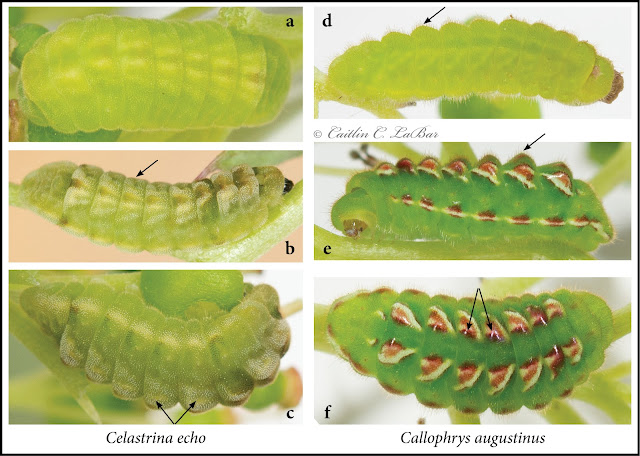

One of the keys to telling apart Celastrina larvae from Callophrys augustinus is their head color: the former is always dark brown, almost black, and the latter is always pale brown. This should have been a clue early on but I didn't notice it on Larva #2 until I reviewed my photos much later. Another marker I noticed, that so far seems fairly consistent in images I've studied, is that the augustinus larvae have a dark patch in the center of the fold just above their head. Celastrina may have a dark marking on either side of that same segment but it always seems to be lighter in the center, essentially a reverse from augustinus. These and other identification markers are described in the following images.

|

| Celastrina have a dark brown head (left) and no dark patch in the center of the segment above the head, while augustinus are the reverse: a pale brown head and a dark patch on the first segment. |

|

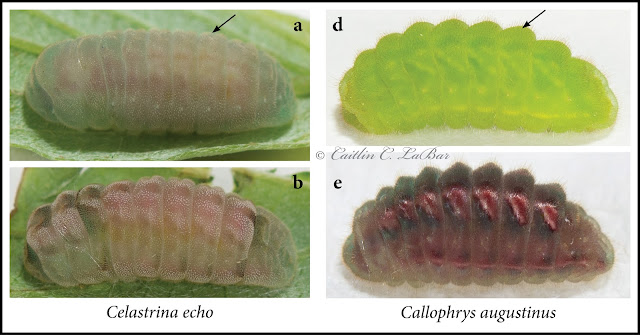

| The relatively smooth segments of Celastrina larvae compared to the ridged appearance of augustinus is best seen in the pre-pupal stage, such as those shown here. |

In summary, while a sample size of six is rather small to confidently say this overwintering method was a raging success, I will definitely be employing it in the future and look forward to better success rearing Celastrina asheri the next time around!

Nicely done. And fantastic photos, as always!

ReplyDelete